“Where did the money go?”

It’s a question I’ve been asked more times than I can count.

And for longer than I care to admit, I didn’t have a clean answer.

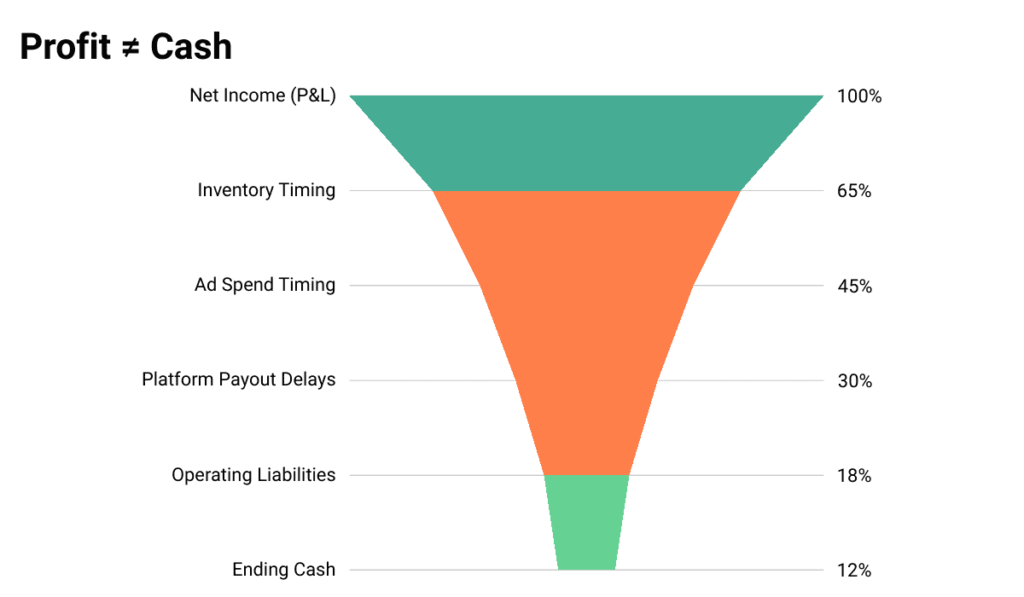

The problem isn’t unique to ecommerce bookkeeping, but bad ecommerce bookkeeping makes it surface faster. A business can be profitable on paper, pay taxes on that profit, and still feel increasingly cash-constrained.

Across hundreds of sets of books I’ve worked on, the pattern is consistent.

The financial reports look complete.

The tax return gets filed.

Nothing is “wrong” in the traditional accounting sense. And yet the same question keeps coming back.

That gap is cash flow — not the statement, but the movement. And most ecommerce bookkeeping systems aren’t designed to explain that movement.

The timing, direction, and accumulation of cash through the business.

Most CPAs are never asked to answer that question. Their job ends when the QuickBooks ties out, and the compliance requirements are met. From a regulatory perspective, that’s success.

But something important is missing. Accounting is often treated as a compliance function. In reality, compliance is only one constraint within it.

Accounting is fundamentally a data function.

And when it’s designed primarily to satisfy compliance, it often fails at the job founders actually need it to do.

Once entrepreneurs ask, “Where did the money go?” the next questions come quickly. And they’re rarely accounting questions in the traditional sense.

These aren’t accounting questions — they’re operating questions.

They sound more like this:

These are not edge cases. They are the core decisions that determine whether an ecommerce business grows or stalls. And yet, most financial systems are not built to answer them.

Instead, accounting systems are designed to explain what has already happened. They summarize outcomes after the fact, once timing differences have settled and uncertainty has been removed. That’s useful for compliance and reporting.

It’s far less useful for deciding what to do next. When founders need forward-looking answers, they end up checking Shopify, ad platforms, and dashboards — each having its own slight discrepancy.

The result isn’t clarity. It’s fragmentation. Business owners have plenty of numbers, but very few answers. The problem isn’t missing data — it’s that most ecommerce bookkeeping systems were never designed to support decisions.

And because the system can’t answer them, founders stop expecting it to. That’s the real failure.

The first thing that breaks when accounting is treated purely as compliance is timing.

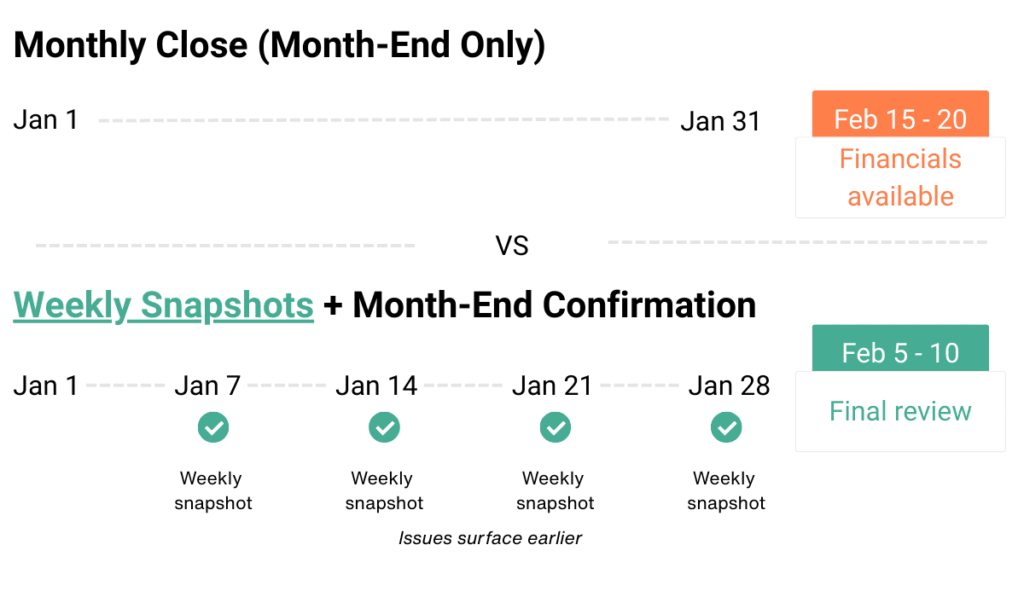

Most ecommerce bookkeeping is reviewed monthly—often two to three weeks after the month ends. Sometimes quarterly. In the worst cases, only once a year. That means decisions made on January 1st aren’t evaluated until mid-February or later.

In practice, that gives business owners about twelve chances a year to notice a problem and react. By the time they do, the issue is often fifty days old.

That delay isn’t just slow. In an ecommerce business driven by ad spend, inventory purchases, and platform payouts, this information becomes largely irrelevant. The decisions that caused the numbers were made long before the numbers were reviewed.

Timing issues also create another problem: bookkeeping mistakes.

When bookkeeping is treated as a mad scramble to get reports out the day before they’re due, accuracy suffers. Transactions are rushed. Classifications are guessed. Reconciliations are forced to tie. Errors get buried instead of corrected. Those mistakes then compound month after month.

This is why monthly-only bookkeeping doesn’t work. This is why weekly ecommerce bookkeeping creates earlier visibility and faster course correction.

The solution isn’t fully closed weekly books. That’s unnecessary and unrealistic. What works in practice is frequency without finality.

Bookkeeping should happen weekly, if not daily, with month-end used to finalize—not discover—the numbers.

More frequent bookkeeping provides real advantages:

What actually works is a two-layer system:

The solution:

You get the month-end faster by doing more work during the month.

Faster financials don’t come from rushing at month-end. They come from structured, weekly or daily bookkeeping that turns month-end into a confirmation step, not a scramble.

The second thing that breaks is the structure.

A lot of ecommerce bookkeeping isn’t really a system. It’s a collection of tasks: reconcile this, categorize that, fix whatever looks wrong at month-end, and hope it holds together.

Weekly insight isn’t achieved by working harder at the end of the month or rushing incomplete numbers out the door. It requires a system designed for timeliness from the start.

That system has to reliably support five functions.

The information needed to make core operating decisions is consistently present. Sales, refunds, fees, inventory movement, and ad spend are visible enough to evaluate tradeoffs, even if some details are finalized later.

Action items that enforce completeness:

Without completeness, every other insight is built on partial information, leading to poor decisions.

Transactions match source activity and are recorded in the correct accounts. Sales, fees, refunds, ad spend, inventory, and platform charges land in buckets that actually reflect how the business operates.

Action items that enforce accuracy:

Accuracy means the numbers reflect what actually happened — in the right place — so trends can be trusted over time and clean books are maintained without constant cleanup.

Balances reflect economic reality, not placeholders. Inventory, cost of goods sold, and liabilities are directionally correct and stable enough to trust.

Action items that enforce valuation:

Valuation means balances reflect what the business actually owns and owes — not what’s easiest to record. This is vital for cash flow forecasting

Activity is recorded in the correct period. Timing errors are often the real reason profitable businesses feel cash-poor.

Action items that enforce cutoff:

Cutoff ensures results reflect when the activity actually happened, not when the cash happened to move.

Financials are structured to support decisions, not just reporting. The format reflects how the business is actually run, not how the software defaults.

Action items that enforce presentation:

Presentation determines whether financials explain what happened or simply prove that something happened.

The solution:

Standardized SOPs that translate accounting rules into repeatable weekly and month-end workpapers, so the numbers are both accurate and usable before decisions are made.

Monthly reviews tell you what happened. They rarely tell you in time to change the outcome.

When paid media, inventory, and platform fees drive results, monthly reviews lag reality, slowing course correction and making it more expensive. By the time an issue shows up in a month-end report, the cash impact has already compounded.

The practical fix is a weekly operating review built around a small number of decision-driving metrics — most importantly, contribution margin.

Weekly review isn’t about precision or a full financial close. It’s about shortening the feedback loop.

Used correctly:

Contribution margin works well in this role because it moves immediately when selling or advertising behavior changes. It answers whether growth is economically working before fixed costs distort the picture.

The details of how contribution margin is calculated matter — and they need to be consistent — but the point here is cadence, not mechanics. Weekly review is an early-warning system. A monthly review is a reporting system.

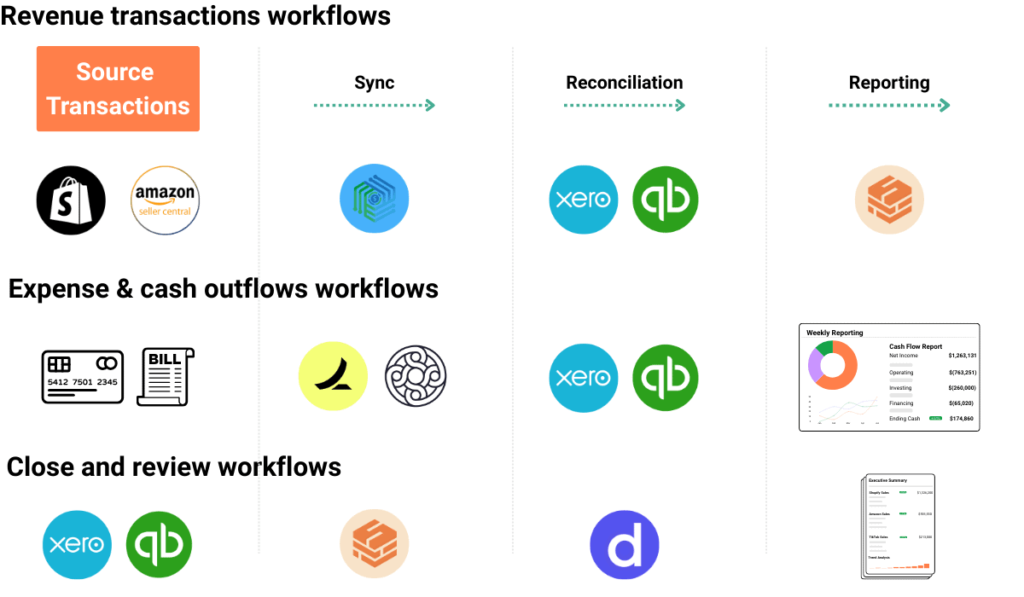

None of the previous fixes work if bookkeeping is still manual at its core.

When transaction capture, reconciliations, and reporting rely solely on human effort, the system breaks down under even moderate complexity. Weekly review becomes unrealistic. Errors compound. And most of the team’s time is spent moving data rather than taking action on it.

Automation is what makes discipline possible at scale. It allows teams to streamline how data flows into review and decision-making without increasing manual work.

Not automation as “set it and forget it,” but automation that ensures activity is captured consistently, routed predictably, and ready for review.

The accounting software is still the spine. QuickBooks, Xero, or NetSuite is where everything ultimately lands. But out of the box, neither is designed for ecommerce complexity or operational review.

Modern banking platforms like Mercury also matter here — real-time feeds and cleaner transaction metadata make weekly visibility and reconciliation far easier than traditional banks.

To make the system usable:

The goal isn’t perfection at ingestion. Its completeness and consistency allow the review to happen without first asking “what’s missing?”

Alongside staples like QuickBooks, newer ecommerce-focused tools — such as Fulfil.io and similar platforms — are worth checking out. They’re designed specifically for ecommerce data flows and can be a good fit for businesses with more complex Shopify inventory and fulfillment needs.

For many ecommerce businesses, tools like Synder, A2X, and Link My Books play a critical role in making accounting workable at scale.

These tools sit between platforms like Shopify, Amazon, and Stripe and the accounting system, handling high-volume transaction details that would otherwise be impractical to manage manually.

Used correctly, they:

Speed is only one benefit. Consistency is the bigger one. Reliable transaction flow shifts review from reconstruction to interpretation.

As with any bookkeeping automation layer, these tools still require:

They don’t replace accounting judgment. They make it easier to apply it consistently in an ecommerce environment.

Revenue tools tend to get the most attention in ecommerce accounting, but inventory and payables are where cash usually breaks first.

Inventory management systems — whether dedicated tools like Cin7 or native inventory modules in Xero or QuickBooks — exist to anchor economic reality. They control when inventory is recognized, how cost of goods sold is calculated, and how much cash is tied up before revenue is earned. Without a reliable inventory layer, margins look volatile, and cash-drain explanations are hard to justify.

Accounts payable and spend management tools, such as Ramp or similar platforms, play a different role. They surface obligations early. Bills, card spend, and approvals create liabilities before cash moves, which is exactly what makes weekly visibility possible. When payables only appear once money leaves the bank, cash planning is already too late.

Together, inventory systems and AP tools ensure that:

They don’t replace the accounting system. They enable the accounting system to reflect what the business has already committed to.

Automation matters just as much outside the GL.

Close workpapers are where judgment lives. Without structure, reviews become subjective and inconsistent.

A functional system uses:

Workpapers shouldn’t be static documents. They should be living checklists tied directly to system outputs, ensuring the same questions are answered every period.

This is where automation enforces behavior:

Tools like Numeric, Double and similar close-management platforms are worth evaluating here, as they’re designed specifically to standardize close workpapers and enforce consistent review workflows.

Reconciliations are one of the highest-friction areas in ecommerce bookkeeping.

This is where AI-assisted workflows actually help—not by replacing judgment, but by narrowing the problem space.

Examples:

The key requirement:

AI assists reconciliation; it does not decide classification or override controls.

When used correctly, this reduces noise and allows reviewers to focus on what changed and why.

Custom reporting doesn’t need to live inside the accounting system.

Tools like Superjoin and Amp are commonly used by ecommerce teams because they integrate directly with Shopify and accounting data and solve a few very practical reporting needs:

Superjoin works well as a reporting layer because:

The mistake is building one-off dashboards. The goal is repeatable views that answer the same questions every time.

Automation fails when it’s applied too early or too broadly.

The correct sequence is:

Automation doesn’t fix a broken system. It enforces a good one.

The solution:

Use automation to standardize inputs, enforce process discipline, and reserve human time for review and decision-making — not data entry.

Sales tax breaks ecommerce books in two ways.

Sales tax is one of the most thankless jobs in accounting. It doesn’t improve margins. It doesn’t help growth. It doesn’t feel strategic. So it gets pushed down the priority list.

That’s exactly why mistakes here lead to real, immediate consequences.

From an accounting perspective, sales tax should be boring and visible.

That means:

When this isn’t done, sales tax payments feel like surprises instead of settlements. Cash suddenly leaves the business, and no one understands why.

Sales tax doesn’t affect profitability — but it directly affects cash. That alone makes it an operating concern, not a once-a-quarter chore.

In practice, many ecommerce businesses:

This works until it doesn’t.

Sales tax errors don’t compound quietly like some accounting issues. They escalate. Notices arrive. Accounts get flagged. The consequences are faster and less forgiving than most other bookkeeping mistakes.

Sales tax is not a good use of a founder’s or operator’s time.

There are mature solutions designed specifically for this:

The exact tool matters less than the decision to stop DIY’ing it.

What matters is:

When sales tax is handled properly:

Sales tax should be operationally boring. If it’s stressful, it’s usually because it isn’t embedded into the system.

The solution:

Treat sales tax as a standing operating liability and delegate execution to tools or services designed to handle it — because mistakes here have real, fast consequences.

Most ecommerce bookkeeping isn’t wrong because the math is off.

It’s wrong because the system is built to document the past, not support decisions in the present.

Clean books, on-time filings, and reconciled accounts are table stakes. What actually matters is whether the system explains what changed, why it changed, and what to do next—before those decisions become irreversible.

That requires:

When bookkeeping is designed this way, financials stop being something you check and start being something you use.

If this is something you want to build internally, this article lays out the bar.

And if you’d rather have it designed, implemented, and reviewed for you, that’s the work we do.

Either way, the goal is the same: a bookkeeping system that actually keeps up with how an ecommerce business operates.